I posted in mid-January about the low snowpack in parts of Alaska and some of the potential impacts. In the five weeks since then conditions have only slightly changed, and some of the potential impacts are now actual impacts. This is a quick update focused on the Alaska situation.

February Snowpack

The snowpack snow water equivalent (the amount of water in the snowpack) from the ERA5-Land reanalysis is shown in Fig. 1. Based on this analysis (the nominal spatial resolution is about 100 km² per grid cell), the snowpack is very low to non-existent over a large portion of southwest Alaska from the Alaska Peninsula northeast through the Bristol Bay area and into portion of the middle and upper Kuskokwim River valley. The lower Kuskokwim valley snowpack is low but not quite as low relative to the 30-year median as it was in early January. Low or no snowpack is also found in the Kodiak Island area and much of Southeast Alaska, though at low elevations this is not especially unusual. In contrast, most of Interior Alaska and Brooks Range shows near to above normal snowpack, and a fairly large area north and northwest of Fairbanks is well above normal.

The situation in Southcentral Alaska is extremely complex: the western edge of the Kenai Peninsula northward across metro Anchorage and just into the lower Mat-Su area has very low snowpack, but higher than average snowpack is found in the mountains in close proximity.

The Alaska Snow Survey Report for February from the Natural Resources Conservation is posted here and provides in situ measurements from both SNOTels (automated observations) and manually measured snow courses as of about February 1. In Southcentral the observation network is, by Alaska standards, pretty dense. Just in the greater Anchorage area, the February 1 snow water equivalent was 0 to 10 percent of normal at sites below 1300 feet MSL but 80 to 150 percent of normal at elevations above 1800 feet. This kind of strong elevation dependence is common in Southeast Alaska but more unusual in Southcentral. In the lower Mat-Su Borough, an area that is prone to impactful early summer wildfires (e.g. Millers Reach in 1996 and Sockeye in 2015), snowpack is minimal in the immediate Palmer and Wasilla areas but increases both in elevation and in even a little north and east, with well above normal snowpack north of Willow (Susitna) and east of Chickaloon (Matanuska).

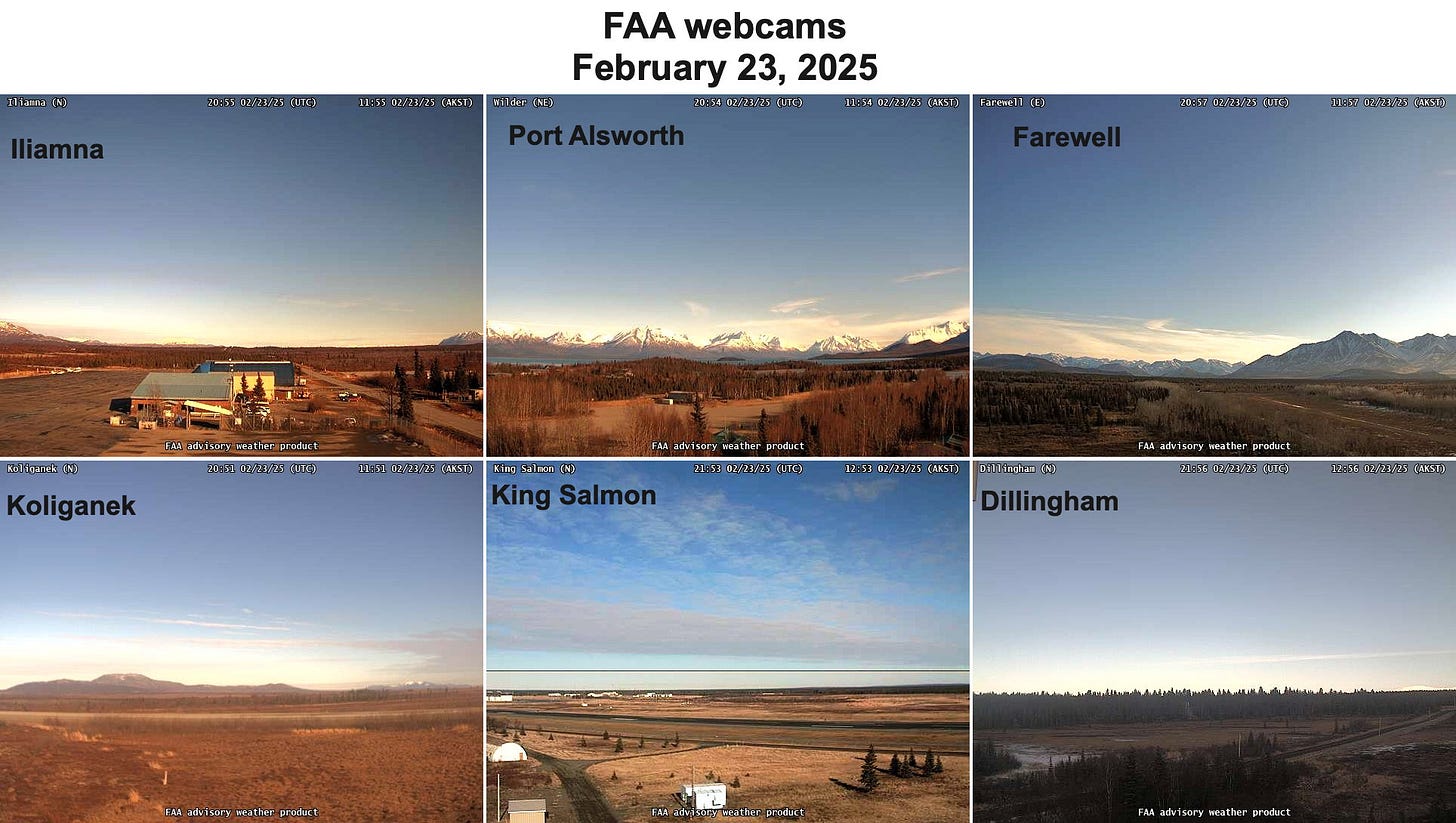

There are very few snow measurements of any type in southwest Alaska, so Fig. 2 presents a collection of FAA webcam images from selected locations Sunday afternoon, February 23. These images correspond well with very low snowpack areas depicted in Fig. 1.

Impacts

One impact of the “localized” low/snow is that for the fourth time since 2003, the restart of the Iditarod Sled Dog Race has been moved from Willow to Fairbanks (the ceremonial start will still taken place in downtown Anchorage), and this means the first couple hundred times of trail are different than usual (once teams get to Galena the route will run along the usual Iditarod trail, though with an extra loop from Kaltag to Shageluk). This decision was made not because of low snow in Southcentral but because a stretch of trail between the Rohn checkpoint and the Salmon River, just north of the Alaska Range crest, has no snow cover. This includes the notorious Farewell burn area but extends across a larger area this year. This was an obstacle in the recently completed Iron Dog Snow Machine race but teams were able to push through. The webcam image from Farewell in Fig. 2 is close to this area.

The potential influence of the low snowpack on the upcoming wildfire season is getting media attention in Alaska, and this has prompted the Alaska Interagency Coordination Center to issue the first Seasonal Outlook for 2025 much earlier than usual. The lack of snow cover at this point in the season in southwest Alaska is especially concerning because it’s getting late in the winter to have much chance of getting enough snow to make much of difference, and this region had unprecedented wildfire activity during early summer 2022: the Bristol Bay area burned more acreage that summer than the combined area burned in the 72 years between 1950 to 2021. All other things being equal, early snow melt gives tundra and boreal forest surfaces more time to dry out. Of course, wildfires require both dry fuels and a spark to get going and expand, and that will depend on the day-to-day weather from April into June.

Did a warm, wet winter cause the high elevation variation? Lots of rain in Palmer (and flooding)