The American Meteorological Society’s annual “State of the Climate” report was released on August 22. Issued every year since 1996, the AMS report is one of several issued by meteorological organizations recapping the global climate.1 Selected highlights of 2023 State of the Climate appear in an accessible climate.gov post here. The complete report, all 482 pages of it, is freely available here.2

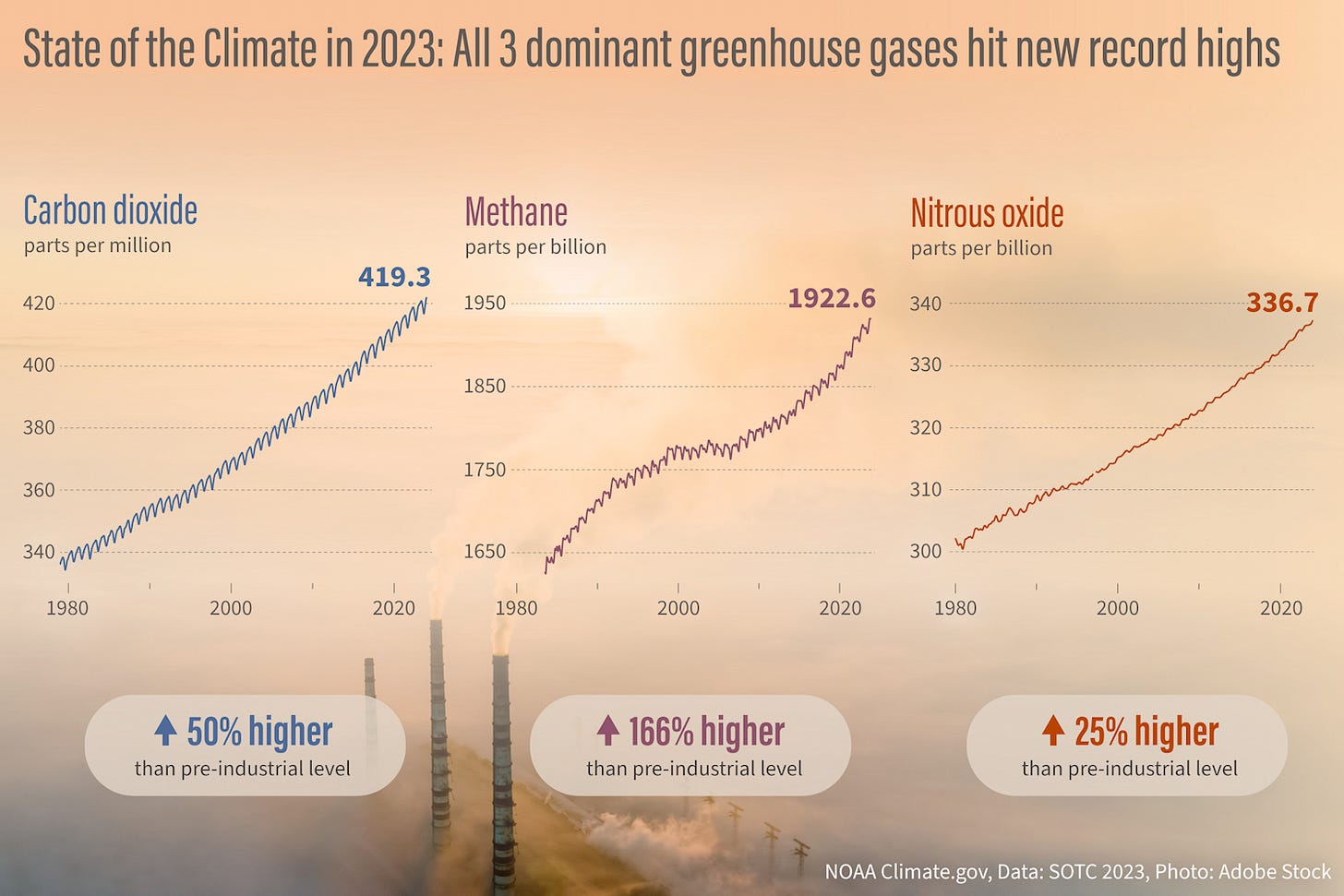

The primary value of the State of the Climate report isn’t that there is much “breaking news”, but rather it is a peer-reviewed compendium of a wide range of contemporary, climate-related information. For example, Fig. 1 is an example of the kind of information in the report. Need a citable source for greenhouse gas concentration and trend? Here you go.

Since the report has been issued for many years, it’s also a ready source for the outcomes of specific climate events. Can’t recall the large-scale climate impacts of the 2015-16 super-El Niño? The 2016 State of the Climate report has them.

The Arctic

The Arctic gets its own chapter every year in the State of the Climate and the 2023 edition is here. The content, to some extent, follows NOAA’s Arctic Report Card (ARC) except that the “State of the Climate” covers the calendar year, while for most physical parameters the ARC coverage is the October to September period in order to allow for a December release. My post about the 2023 Arctic Report Card is here and my 2023 Arctic annual climate summary, focused on temperatures, precipitation and snowfall was posted here in early January.

Notable headlines for 2023 include the warmest summer (July-September) of record, the second warmest autumn (October-December) and the fourth warmest calendar year overall (since 1900). We also include a separate side-bar highlighting some impacts during the record warm summer. This included an extreme rain event in parts of Norway and Sweden and of course the record wildfire season in Northwest Territories, Canada. While the September 2023 minimum extent was “only” the fifth lowest, a record high number of vessels completing a trip through the Northwest Passage (through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago) and the second highest number completing the Northern Sea Route (across the northern Russian coast from Europe to the Pacific Ocean).

Several sections are included in the 2023 State of the Climate Arctic chapter that were not in the Arctic Report Card, including sections on Glaciers and ice caps outside Greenland, Permafrost, and Atmospheric circulation.

Unsurprisingly, glaciers continue to thin, with the 2022-23 season showing the second highest combined loss at more than two dozen glaciers around the Arctic (including Alaskan glaciers near the Gulf of Alaska). Overall, pan-Arctic glacier melt 2021 to 2023 contributed about 1mm to sea level rise.

Permafrost temperatures generally show continued warming, though some of the “cold permafrost" sites in Alaska, where the 15 to 20 meter depth temperature is still lower than -3C, show slight cooling in the past couple years, reflecting cooler annual temperatures since 2019.

Full Disclosure:

I have served as one of the general editors for the AMS “State of the Climate” Arctic Chapter since 2020 and been a co-author on the Surface Air Temperature section since 2015.

The World Meteorological Organization’s “State of Global Climate” also reports on the calendar year and is typically issued in March or April. The Arctic coverage is more limited than the AMS State of the Climate or the Arctic Report Card. The 2023 report is here. NOAA/NCEI and the European

Because the State of the Climate is published as a supplement to the American Meteorological Societies’ flagship publication, the Bulletin of the AMS (BAMS), parts of the report are fairly technical and are in places jargon-heavy.

Rick, your work is much appreciated. Thank you.

Alaska warming brings consequences!

"Permafrost is releasing methane where you don't expect it"

https://fm.kuac.org/science-and-technology/2024-08-13/permafrost-releasing-methane-where-you-dont-expect-it

Dr. Katey Walter Anthony is known for her methane studies. Walter Anthony found that these bulbs or balloons of gas were forming where the permafrost had thawed dozens of feet deep, making the stored carbon in the soil easier for the microbes to get to. ... The Yedoma soils are composed of many meters deep of decaying ancient grasslands, so there is a lot of carbon there. “It's a unique type of permafrost. It's only about 7 percent of the permafrost region in the north, but the amount of carbon it stores is closer to 25 percent,” said Walter Anthony. "So, Yedoma is kind of a hotspot bank account for permafrost carbon.” In the study published last month in the journal Nature Communications, Walter Anthony and her UAF colleagues identified some Alaska upland places are actually surprisingly large methane sources. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-024-50346-5