Sea ice changes over the past few decades in the Arctic are mostly dramatic in autumn. The most widely reported Arctic “bell-weather” climate change metric, the annual sea ice extent minimum, has declined by 46 percent between 1979 and 2023 (for 2023 in context see my post here). The loss of all that ice by late summer has a profound effect on the Arctic autumn climate. As solar heating becomes negligible, by early October north of 80N and late October north of 70N, the exposed water becomes an important source of heat to the Arctic atmosphere.

Arctic-Wide Ice Changes

To start with a concrete example, Fig. 1 compares the October average daily sea ice concentration for 1985 and 2022 across the Arctic using National Snow and Ice Data Center passive microwave data. The differences are apparent even at this scale, with large decreases north and northwest of Alaska and north of the Russian Asian Arctic.

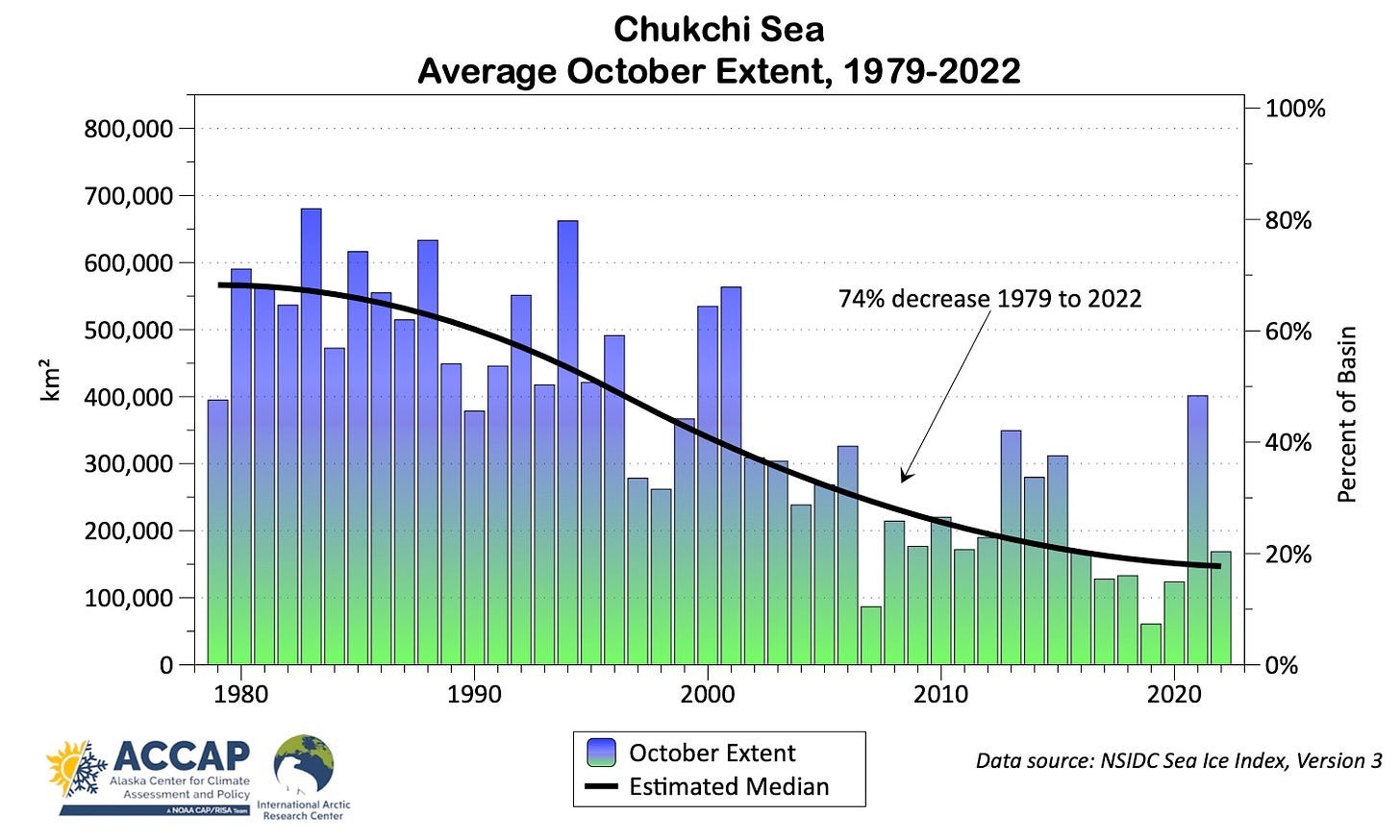

Figure 2, courtesy Z. Labe (@ZLabe@fediscience.org), shows the trend in October sea ice concentration during the satellite era. The largest changes are in the Chukchi Sea and the Barents and Kara Seas but ice concentration is trending down everywhere along the margins of the Arctic ice pack: trends in the high Arctic Ocean are minimal because each concentrations are were and are still very high.

Changes near Alaska

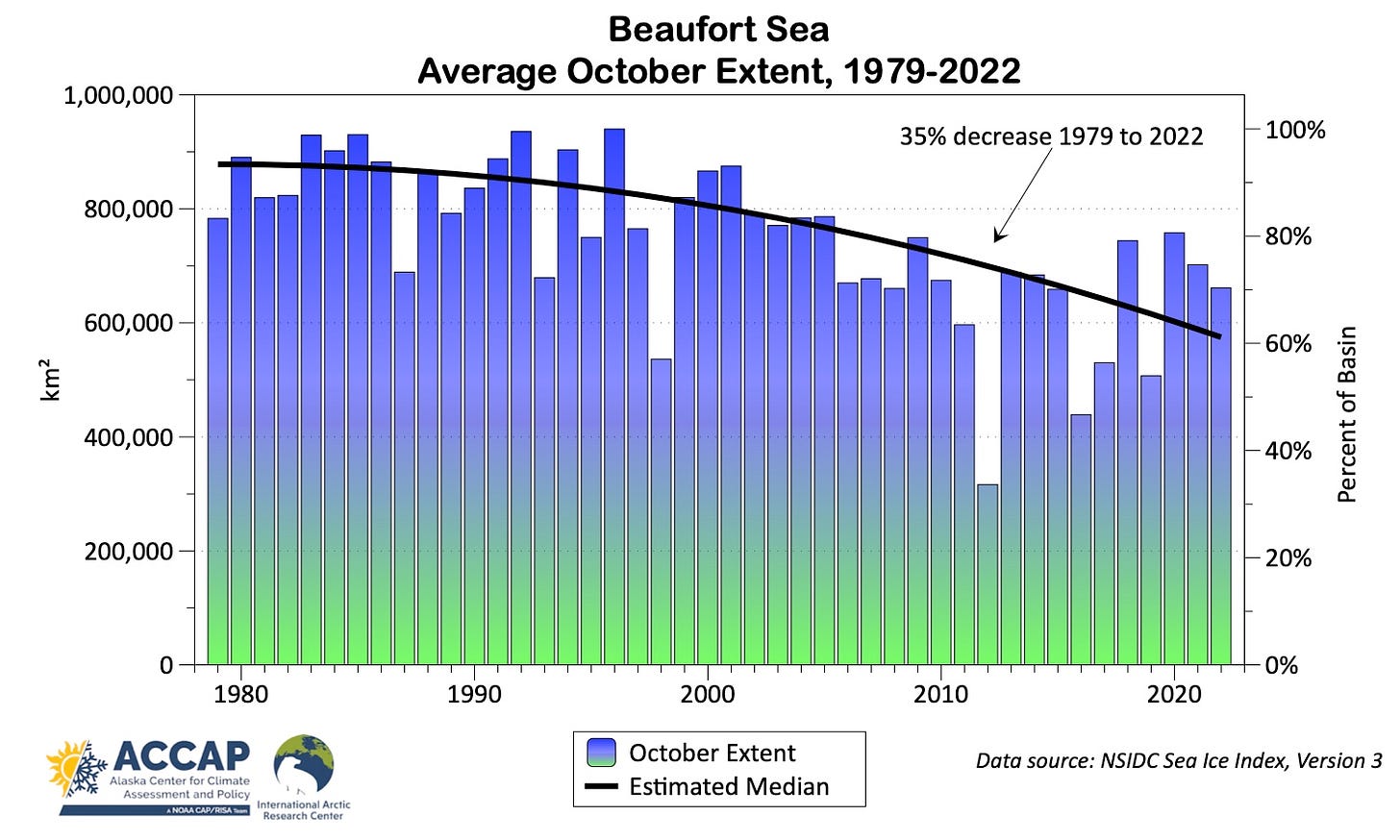

Taking a look how October ice extent as varied in the seas near Alaska, we find, as with nearly all climate metrics, significant year-to-year variability superimposed on the longer term trend. In the Beaufort Sea (Fig. 3), prior to the late 1990s, sea ice extent was typically in excess of 90 percent of the basin (as defined by NSIDC), though that has not occurred since 2001. Overall, the 35 percent decrease in median extent translates to more than 250,000 km² of addition exposed water surface.

The changes in the Chukchi Sea (Fig. 4) are even more dramatic, which is what we expect based on Fig. 2, though the pattern is similar to the Beaufort Sea. One difference though is that the estimated median is not decreasing as rapidly now as in the late 1990s and early 2000s, with little overall change since 2010. This is not surprising: the Chukchi Sea minimum extent in summer is approaching zero in many years nowadays, so the October extent is starting out at close to the same (near zero) level, in contrast to before 2010, when end of summer extent was much more variable.

In the next post I’ll look at temperature changes to illustrate the dramatic autumn climate impact of these changes in sea ice.