November was a very mild month across all of Alaska and indeed much of the Arctic, finishing off an impactful autumn. This posts focuses on Alaska using mostly station-based observations. Once the reanalysis data for November posts I’ll have a Arctic-wide review of Autumn 2023 climate.

Seasonal highlights

Figure 1 is my social media graphic with selected Autumn 2023 highlights around the Alaska. What show up here is dictated both by what’s happened and by considerations for what fits on the graphic, and I try to include a mix of impacts and climate stats. The landslide at Wrangell on November 20th that claimed the lives of six people is the most tragic of the highlights. This is the second fatality-causing landslide in Southeast Alaska in the past three years (the other being the December 2020 slide at Haines that claimed two lives). There were other landslides in Southeast Alaska during the November 20th storm that blocked roads. Also concerning is the poor state of river ice in southwest Alaska at the end of the autumn, and Shishmaref, one of Alaska’s most imminently threatened communities, suffered significant coastal erosion in a storm in mid-November.

November Temperatures

Everywhere in Alaska was warmer than normal in November, and except for Kodiak Island and the southeast Kenai Peninsula coast, warmer by a significant margin. Figure 2 plots the monthly departures from the 1991-2020 normal. For much of the Interior this was the mildest November since 2002, while over western Alaska 2017 (and in some places 2020) was milder.

During the cold season especially comparing raw departures from normal across different climates can be misleading. In November, Fairbanks Airport average temperature was 11.6F (6.4C) above normal, while Sitka Airport was “only” 4.1F (2.3C) warmer than normal. However, for both locations this was the fourth warmest November since 1950. The difference is of course that the ocean dominated climate of Sitka severely limits temperature variations, while the continental climate of Fairbanks, with cold season snow cover and little solar heating routinely allows for large variation in temperatures.

For long term climate sites only Deadhorse set a record for highest average temperature in November. In much of Interior and western Alaska either 1979 and/or 2002 were significantly milder. Alaska-wide daily temperatures extremes for the month ranged a high of 64F (17.8C) at Unalaska on the14th to a low of -35F (-37.2C) 20th at Glennallen. Both of these are notable: the Alaska state high temperature for November is 67F (19.4C) last recorded at Annette in 1976. The November low was not impressive for the value but rather the location. Glennallen’s is on an elevated valley and has occasionally reported the state low tempertaure in the late summer, but by November the state’s lowest temperature is usually reported from the Interior or Brooks Range.

November Precipitation and Snow

Precipitation (rain plus melted snow), as is often the case, showed much more variability relative to normal than temperatures. Unfortunately, in-situ precipitation observations are not only far fewer than temperatures but have far more problems. The vast majority of FAA and NWS automated airport weather stations do not consistently report reliable precipitation totals during the cold season. Additionally, there is little to no quality control (near-real time or otherwise) of observations from the vast majority of stations.

With those many caveats, Fig. 3 at least gives us a general idea of precipitation from the climate viewpoint, showing November precipitation as a percent of the 1991-2020 normal. Far above normal totals evident from the northwest Kenai Peninsula northward across Anchorage and into the Mat-Su valley, as well as the Copper River basin. With very few observations, southwest Alaska appears to have seen mostly below normal totals but monthly precipitation above normal in the western Interior, northwest Alaska and North Slope.

Anchorage Airport easily set a new November record precipitation with a total 3.44 inches (87.4mm), which included the excessive snow mid-month and rain in early and late in November. The previous record was 2.84 inches in 1976. Cordova Airport on November 8th measured 6.35 inches (161.3mm) of rain, which is by far the highest calendar day total in November on record.

I wrote about the big Southcentral snow early in the month here, but the second half of November brought only a little additional snow to most low elevations. Anchorage Airport finished up with 39.3 inches (99.8cm), which is a new record for November snowfall, edging out the previous record of 38.8 inches (98.6cm) in 1994. The highest reported snowfall for the month was 70.2 inches (178.3cm) near Girdwood (southeast of Anchorage), which was not a November record.

North of Alaska Range snowfall mostly tracks with precipitation, as there was little or no rain in most places. In the western Interior, the cooperative observer at Galena reported 34.9 inches (88.6cm). Climate records are incomplete since the military withdrew from Galena in 1993, but based on what there is, this month’s total just exceeds the November 1992 record of 34.3 inches (87.1cm). Without any snow measurements at all in western and southwest Alaska all we have to go on are webcam images for a guess at snowpack at a given time, but of course that tells us almost nothing about the associated snowfall.

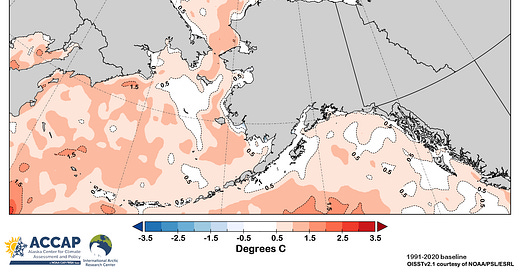

November Sea Surface Temperatures and Sea Ice

For November, sea surface temperatures (SSTs) were generally above normal (Fig. 4) except in the Beaufort Sea where sea ice was in place by mid-month.1 There was still an area in the central Bering Sea close to normal, but in a change from late summer, over most all of the Bering Sea SSTs are now above normal. Gulf of Alaska SSTs are also near to above normal, though not by as much as in the western Bering Sea.

Figure 5 illustrates the change in sea ice near Alaska during November. The month started off with sea ice confined mostly to inside the barrier on the Beaufort Sea coast and near river outlets farther south. While remarkable from an historical perspective, the only unusual thing for the recent years was that the main Beaufort Sea ice pack was still 50+ miles offshore of the Alaska coast. Beaufort Sea ice-over was complete by mid-month, but ice was slow to grow in the southern Chukchi and northern Bering Seas. Kotzebue Sound was still largely open water on November 15th for the first time since 2017. At the end of November, on the Alaska side, sea ice in the Bering Sea was still confined to eastern Norton Sound and near river mouths, while on the Russian side the only ice was in bays off the Gulf of Anadyr. In the Chukchi Sea there was still a continuous path of open water from the Bering Strait to northwest of Utqiaġvik at 72°N.

Technical details:

The High Plains Regional Climate Center mapping tool is available here.

Sea surface temperatures from the OISSTv2.1 dataset available from NOAA/Physical Sciences Laboratory here.

National Weather Service Alaska Region Sea Ice Program analyses available here.

During the cold season, SSTs north of Bering Strait are constrained by sea ice and the lower limit of liquid ocean surface water temperature (-1.8C, 28.8F), which means that sea surface temperatures can’t be too much below normal, and this spreads south during the course of the winter and early spring. Of course this isn’t an issue in the Gulf of Alaska except in the western Gulf land-constrained bays, e.g. Cook Inlet or Kachemak Bay.

Thank you Rick! Great Information!