Spring is a time of rapid transition in Arctic, driven especially by changes in the frozen environment. On land, river ice break-up and melting away of the winter snowpack herald the start of the warm season. Changes come slower to the frozen portions of the northern oceans but are now well underway.

Arctic Sea Ice

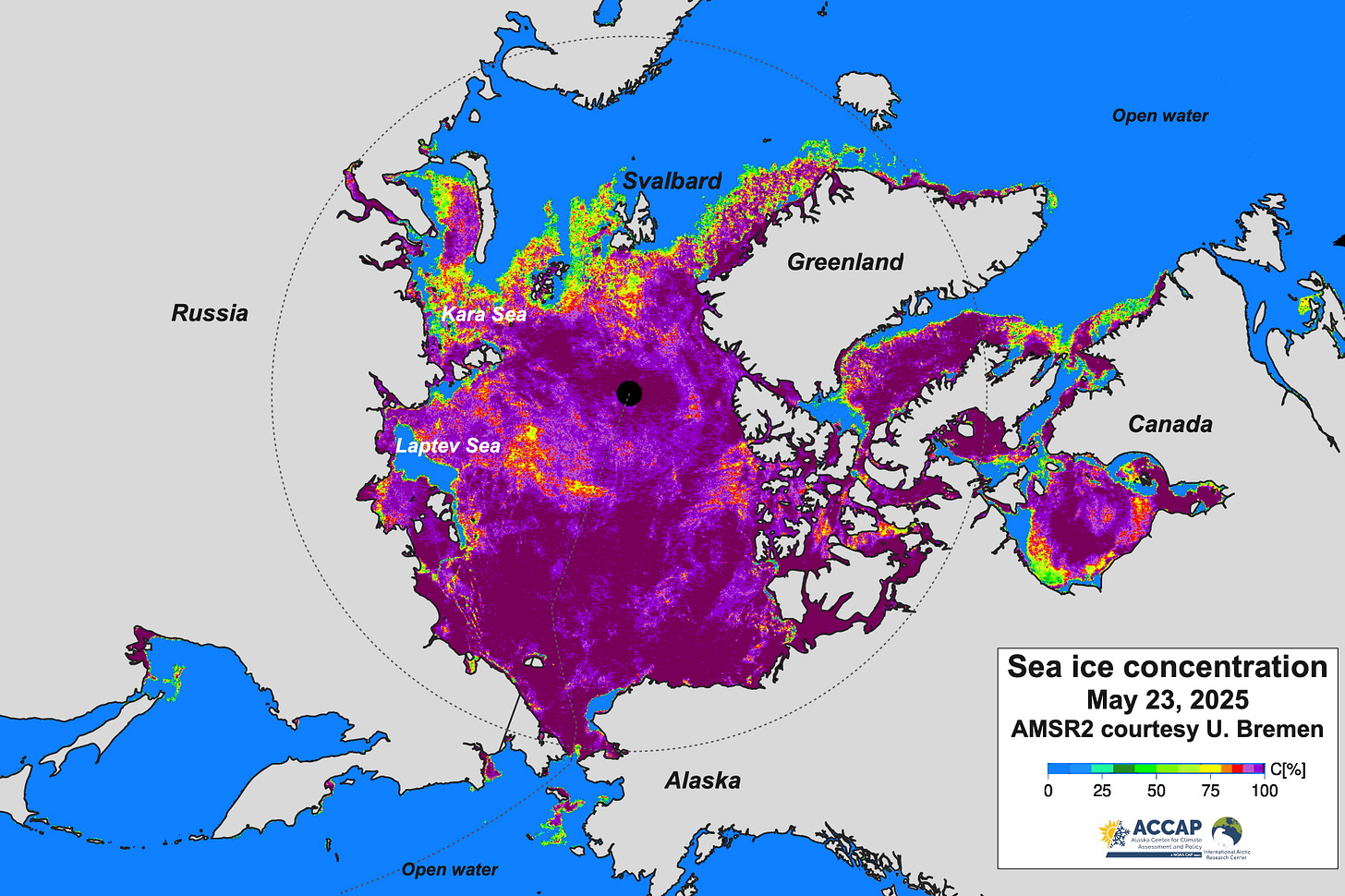

After unusually limited loss of sea ice melt in April (details in my April summary post), Arctic sea ice decline has been fairly typical the first three weeks of May. Figure 1 shows the May 23, 2025 sea ice concentration from the AMSR2 passive microwave data. Arctic-wide sea ice extent is the sixth lowest for the date in both the NSIDC and JAXA analysis, down a bit from the April rank (ninth lowest). As usual these days, there are regional extremes. Currently, there is much more open water in both the Kara and Laptev Seas than usual for this point in the season. The Kara Sea ice extent is the second lowest in the satellite record (only 2020 lower) and the Laptev Sea ice extent is the lowest on record for the date. In fact, in most years since 1979, there has been no open water in Laptev Sea on May 23.

Arctic snow cover

The Spring loss of snow cover is an important event in the higher latitude seasonal cycle because the presence or absence of snow has important ecological, hydrological and weather/climate consequences. The U.S. National Ice Center (NIC) prepares a daily pan-Arctic analysis of the snow and ice extent (I provide more details on NIC analyses in this post). Importantly, this is a categorial analysis: is there snow on the land, yes-or-no and is there ice on water (on the ocean and on freshwater lakes), yes-or-no? Figure 2a shows the May 23 snow and ice extent analysis. The loss of snow since the beginning of May, Fig. 2b, is apparent around the Arctic but especially across Eurasia. Changes in sea ice can also be seen but are not as dramatic.

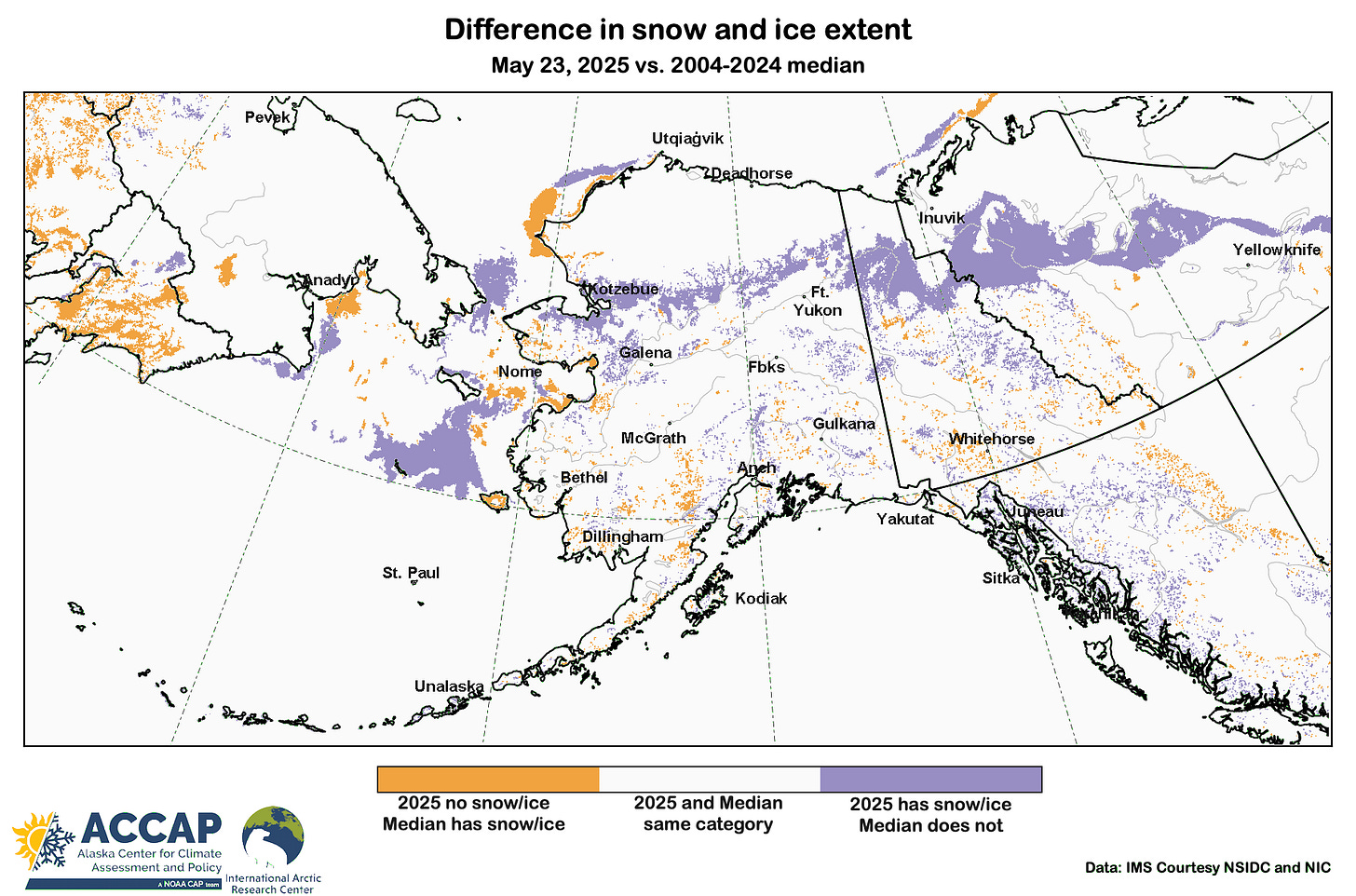

The NIC high resolution snow and ice extent analysis started in 2004, so while we don’t have a full 30-year climate baseline, we do have the most recent 21 years available for comparison. Figure 3 shows where snow and ice extent on May 23 was different from the 2004-2024 median category. Several features stand out. A large portion of eastern Siberia has bare ground when typically there would still be some snow. Much of this area is in the vast Republic of Sakha, Russia, which has experienced several years with extremely large wildfires in the past decade. Parts of the Nordic Arctic also show an early loss of snow. In North America, the northern limit of (lower elevation) snowmelt is consistently south of the 2004-24 median from west of Hudson Bay northwest to the south slopes of the Alaska Brooks Range and right to the Chukchi Sea coast.

Alaska and vicinity snow cover

The same data shown above is presented here, just with a closer view of northwest North America and the Russian far northeast. Low elevation snow cover is about gone in Alaska and the Yukon Territory south of about 67°N except on the northern Seward Peninsula and St. Lawrence Island, where these marine-dominated climates always hold on to Spring snow cover later than inland areas at the same latitude.

The May 23 difference from the 21-year median is shown in Fig. 5. The belt of late-lasting snow across the south slopes of the Brooks Range becomes more prominent in the northern Yukon Territory and Northwest Territories northwest of Yellowknife. There are also indications (the purple speckles) that snow is present later this year than typically the case at moderate elevations in Interior Alaska and the Yukon, which is confirmed in some areas, e.g. Yukon-Tanana uplands east of Fairbanks, by in situ observations.

In the ocean, the ice south of St Lawrence Island shows up as atypical, while the area of open water off the western North Slope coast, while common at this time of year, is a bit larger than usual.

Up in the Skyline/Skyridge area of Fairbanks, the reliable snow piles that usually last through Memorial Day are still there, but barely.

Excellent report as always.