The northern hemisphere winter season has passed the halfway point, so this seems like a good time to check in on the current state of the winter snowpack.1 Of course, in most of the Arctic there are still two to four months yet to come when most or all precipitation will be snow.

Snowfall, snow depth and snow water equivalent (SWE) are all extremely difficult to measure in most Arctic environments due to the combined effects of wind, topography, longevity of snow cover and the complex physics of snow.2 Additionally, automation of weather and climate observations has resulted in the loss in recent years of in situ snow-related observations, which were always more sparse than temperature observations, in the North American Arctic. As a result, this overview relies primarily on reanalysis to assess the current state of the snowpack.

Modeled Snowpack Analysis

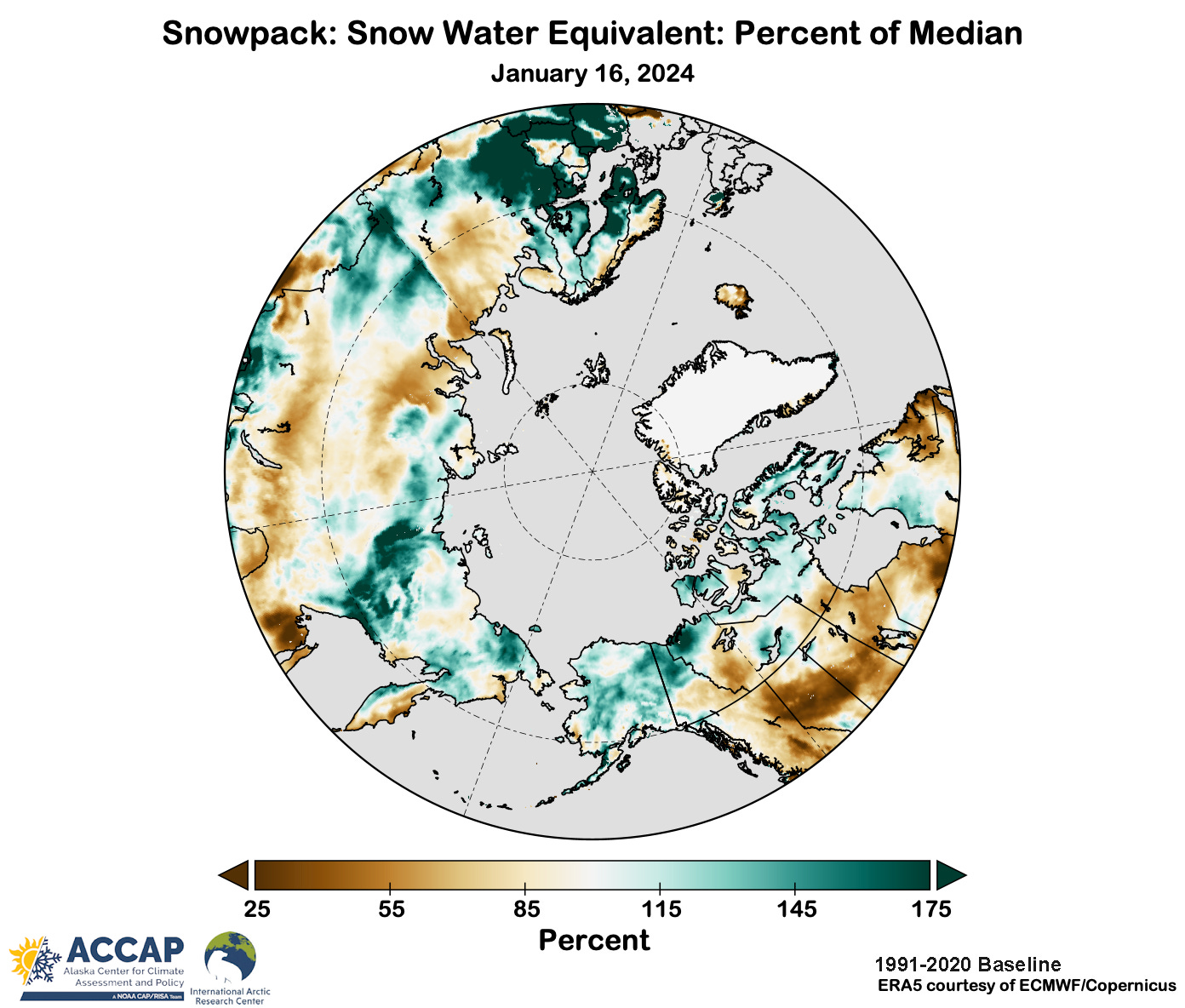

Snowpack as of mid-January 2024 is shown in Fig. 1 was generally above the 30-year median in a wide swath from northeast Russia, across much of mainland Alaska, the northern Yukon and northwest Northwest Territories, and less dramatically across most of Nunavut, Canada. Below median SWE prevailed over the western Russian Arctic, Iceland and southern portions of Arctic Canada.

Figure 2 shows the same analysis as in Fig. 1 but focused on the greater Alaska region. Most of mainland Alaska had near to above normal SWE as of January 16 (some exceptions in western and southwest Alaska), but parts of northwest Canada and Southeast Alaska showed a very different picture: from the southern Yukon Territory east and southward, large areas had much lower snow water equivalent than median (though the Great Slave Lake area in the Northwest Territories saw above median snowpack). While there’s still time to make up some or all of this deficit, if this persists until Spring break-up, that would be a potential important factor for early season wildfire risk for areas in northwest Canada. For southern Southeast Alaska, low mountain snowpack brings the risk of community water shortages if later spring and early summer turn out to be unusually dry.

Snowpack Observations

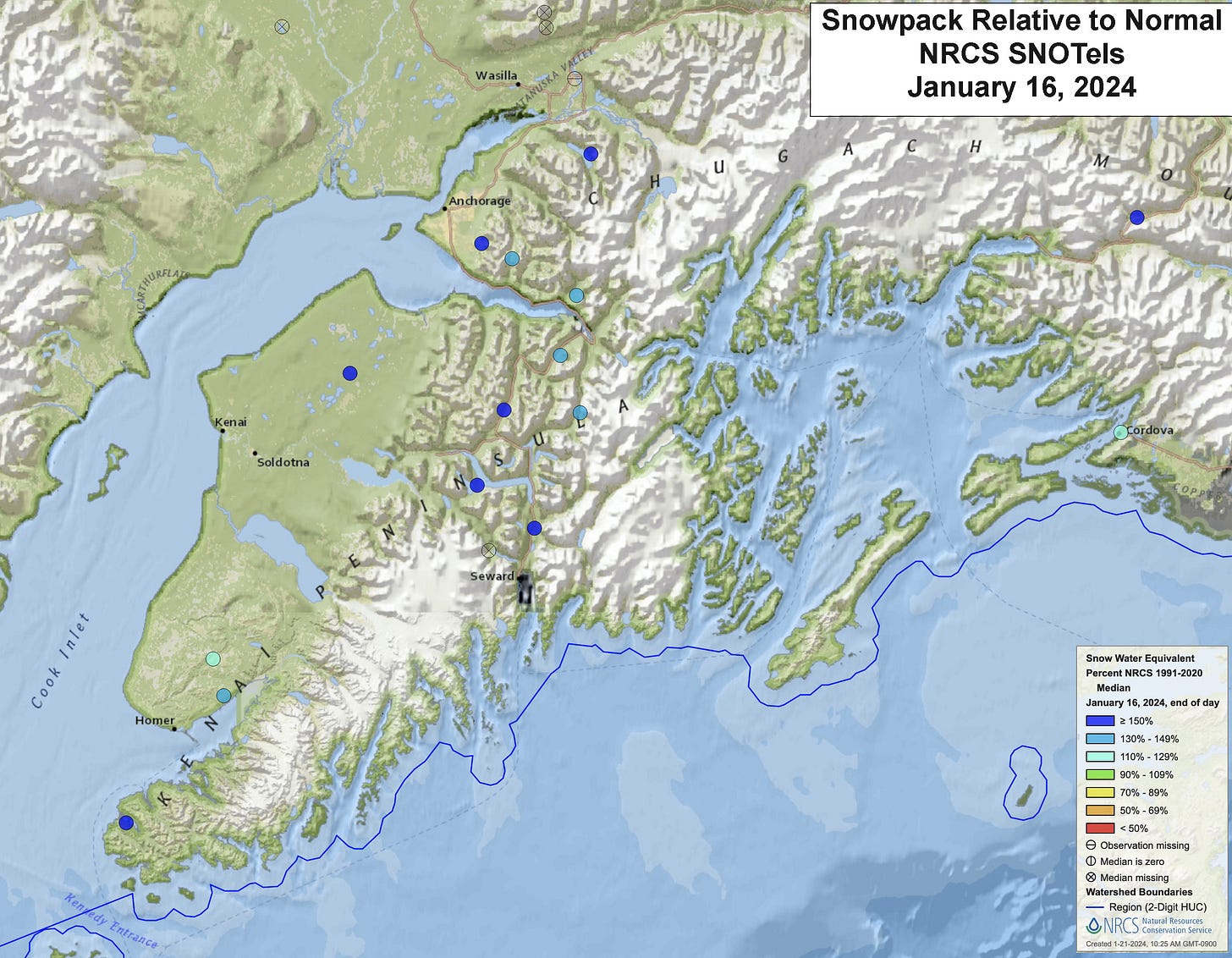

The US Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) is the primary collector of snowpack information in Alaska. NRCS maintains a network of about 50 automated observing platforms in the state that measure snowpack and other environmental variables. These are known as SNOTel, from “Snow Telemetry”. Not all of these sites measure snow water equivalent; of those that do, nearly half are in Southcentral Alaska (there are a couple in Southeast Alaska and the rest in the Interior). Because of the decisive control that the mountains play on precipitation and snow in Southcentral, and because the spatial resolution of the current generation of reanalysis is too coarse to resolve the details in this complex terrain, it’s important to make use of this comparatively high-density observation network.

Figure 3. shows the percent of median snowpack at 15 SNOTel sites in the region. There are also five sites in this region, marked as an Ⓧ, that have short observational history and so lack a climate baseline. The snowpack at all 15 sites is well above median, though in the mountains southeast of Anchorage it’s not quite as far above normal as closer Anchorage and in the northern Kenai Peninsula.

If you look closely at Fig. 2 you’ll notice an area of above median SWE extends from the southern Susitna Valley south across the western Kenai Peninsula, and that is in line with the observations. However, Fig. 2 also shows an area inland from western Prince William Sound with slightly below median SWE. This is not exactly contradicted by the available SNOTel data since this “low SWE” area lies just east of most or all of observations. However, this example highlights the importance of using all the tools in the climate monitoring toolbox.

Technical details:

Reanalysis data from ECMWF/Copernicus. This post uses the ERA5 Hourly Land data available here.

NRCS provides a useful mapping tool for snow related data here.

I usually use “snowpack” as shorthand for “snow water equivalent of snow on the ground”

There are countless publications on snow and snowflake physics and the ins and outs of measuring snow. A couple books that I refer to regularly are:

A field guide to snow. (2020) by Matthew Sturm, University of Alaska Press. Everything you want to know about the physics of snow and why it matters.

The Snow Booklet: A Guide to the Science, Climatology and Measurement of Snow in the United States. (1996) by Nolan Doesken and Arthur Judson. Colorado Climate Center: Colorado State University. The standard reference for how to do snow measurements in the real world. Available as a free pdf, here.