“When is winter?” is one of those questions that climate specialists may fret over, but almost no one else gives a second thought to. It turns out that from a climatological perspective there are a number of ways to define winter (and the other seasons), and here we’ll look at just one alternative definition.

Right up front, the idea that northern hemisphere winter “starts” on the December solstice, about December 21 and runs until the March equinox, about March 22, appears to be primarily a North American concept of relatively recent vintage, though with the rise of easy global communications it’s been picked up elsewhere in recent years. Another widely used definition of the seasons, at least historically, is also based on the sun, but with the solstices as the winter and summer mid-points, e.g. Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night's Dream” is set around the June solstice. As an Interior Alaskan, the concept of solstice-centered seasonal definition resonates. Winter for me is very much associated with the darkest time of year, roughly mid-November to mid-February. By late February, it’s usually still cold, and snow melt is still six to ten weeks in the future, but the daylight hours are rapidly lengthening (nearly 7 minutes a day at 65°N) and the sun is rising high enough in the sky to significantly warm temperatures during the day. That’s quite different than the month around solstice, when there’s no significant daytime heating.

Getting away from solar-based definitions, in climatological work, a common unit of analysis is the calendar month. As a result, northern hemisphere “winter” has long been defined as December through February because for the vast majority of the extratropical northern hemisphere land areas these are the three months with the lowest average temperature. By going to the daily time scale we can refine that “coldest three months” further. We can define “winter” as the coldest quarter of the year, i.e. the 91 days with the lowest average temperature (analogously, summer is defined as the 91 days with the highest average temperature). This is a reasonable definition if we want to keep to four seasons of equal length. That might not best for some purposes, but that’s for a different post.

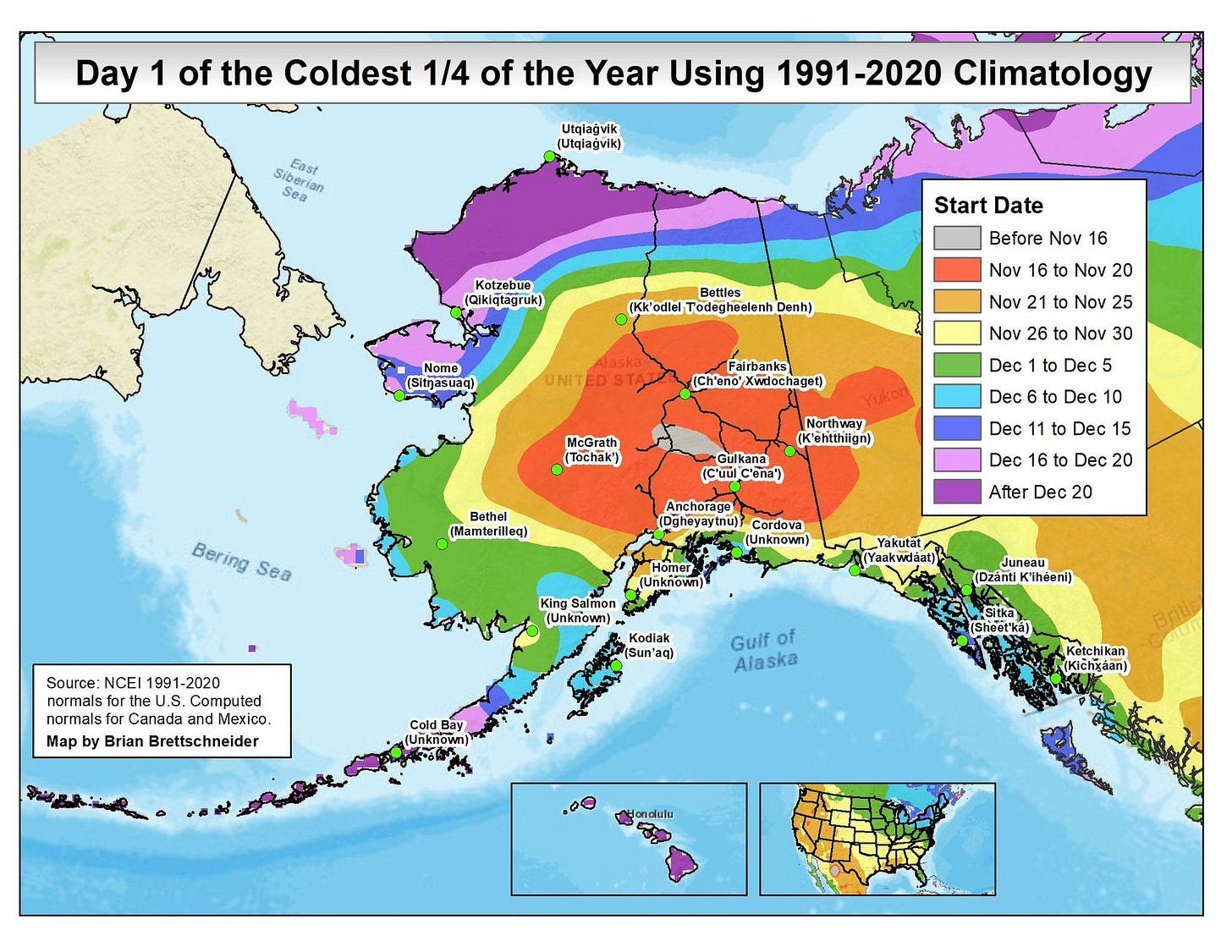

Fig. 1 shows the start date of the coldest quarter of the year for northwest North America. For a large portion of Alaska and the Yukon Territory, “winter” so defined starts in mid to late November, closely following the decline in solar heating. In many areas close to the ocean, the start of winter is later due to lingering summer heat content in the ocean waters in late autumn.

Your eye has probably already spotted possibly the most interesting feature of this graphic, which are the purple shades, denoting a comparatively late start to the coldest quarter of the year. In Alaska, this very late start to winter is a combination of two factors. One is that lingering autumn ocean heat content, and for the Aleutian Islands and lower Alaska Peninsula this is the primary cause of seasonal lag relative to other parts of the state. The other is that nearly all the areas in purple shades are also tundra environments, and from the Northern Bering Sea northward this is a major factor delaying an increase in air temperatures in February and March. As the sun returns and gets higher in the sky, the tundra is close to 100 percent snow covered and much of the vegetation buried. This makes the reflectively (albedo) of the land and adjacent snow covered sea ice extremely high: most of incoming solar energy is reflected right back into space by the snow surface. If you’ve had the experience of flying into Nome or Kotzebue or Utqiaġvik or Deadhorse in March, you know that you better have your sunglasses at hand as daytime can be blindingly bright. That is in sharp contrast to flying into places like Fairbanks or Whitehorse in March, where even though there may well be two or three feet of snow on the ground, the boreal forest is positively dark in comparison to tundra, and so the albedo is much lower and more of the solar energy is going into heating the air near the ground.

What all this shows is as is often the case in life, something that seems simple “everybody knows when winter is” turns out to be more nuanced, and ultimately much more interesting when we look closely at what we’re working to describe.

The coldest three months in coastal California probably start in mid-December. We have the strong ocean effect also, in addition to the winter precipitation or wet season at that time.