Spring Break-Up Flooding

An Complicated Alaska Environmental Hazard

April 2023 finished up as one of the coldest Aprils in the past century for Alaska. The NOAA/NCEI preliminary analysis ranked this as the fourth coldest April since 1925. Temperatures have moderated back toward normal the first two weeks of May, and river ice break-up and the associated risk of flooding is now underway over mainland Alaska. An insightful reader asks: what does a really cold April or extreme cold snaps in early May mean for river break-up?

Flooding during spring across mainland Alaska differs from flooding in the summer in a couple of important ways. Spring flooding is largely the result of melting of snow that has been accumulating five to seven months and the resulting runoff being impounded by ice jams that form in river channels. Spring flooding tends to be most severe on the main stems of big rivers, e.g the Kobuk, Koyukuk, Tanana, Yukon and Kuskokwim Rivers, and more rarely the Copper or Susitna Rivers. In summer and early autumn, flooding from heavy rains often occur on smaller tributaries and less frequently on the main stems of the big rivers.

Naturally, flooding that impacts people and infrastructure gets the most attention. But significant ice jam flooding also occurs far from communities. For example, in May 2022, a long-lived ice jam formed on the middle Yukon River not far above Grayling, backing up water and causing flooding for more than 20 miles above the jam. However, because there are no communities in the 100 miles between Kaltag and Grayling, this probably would not have been documented by hydrologists prior to the the advent of high resolution satellite imagery.

Past Spring Flooding

Break up ice jam flooding is one of the most important environmental hazards along Interior and southwest Alaska rivers and occasionally causes extensive property damage and displaces residents for months. Here are some of the Springs with the notable break-up floods:

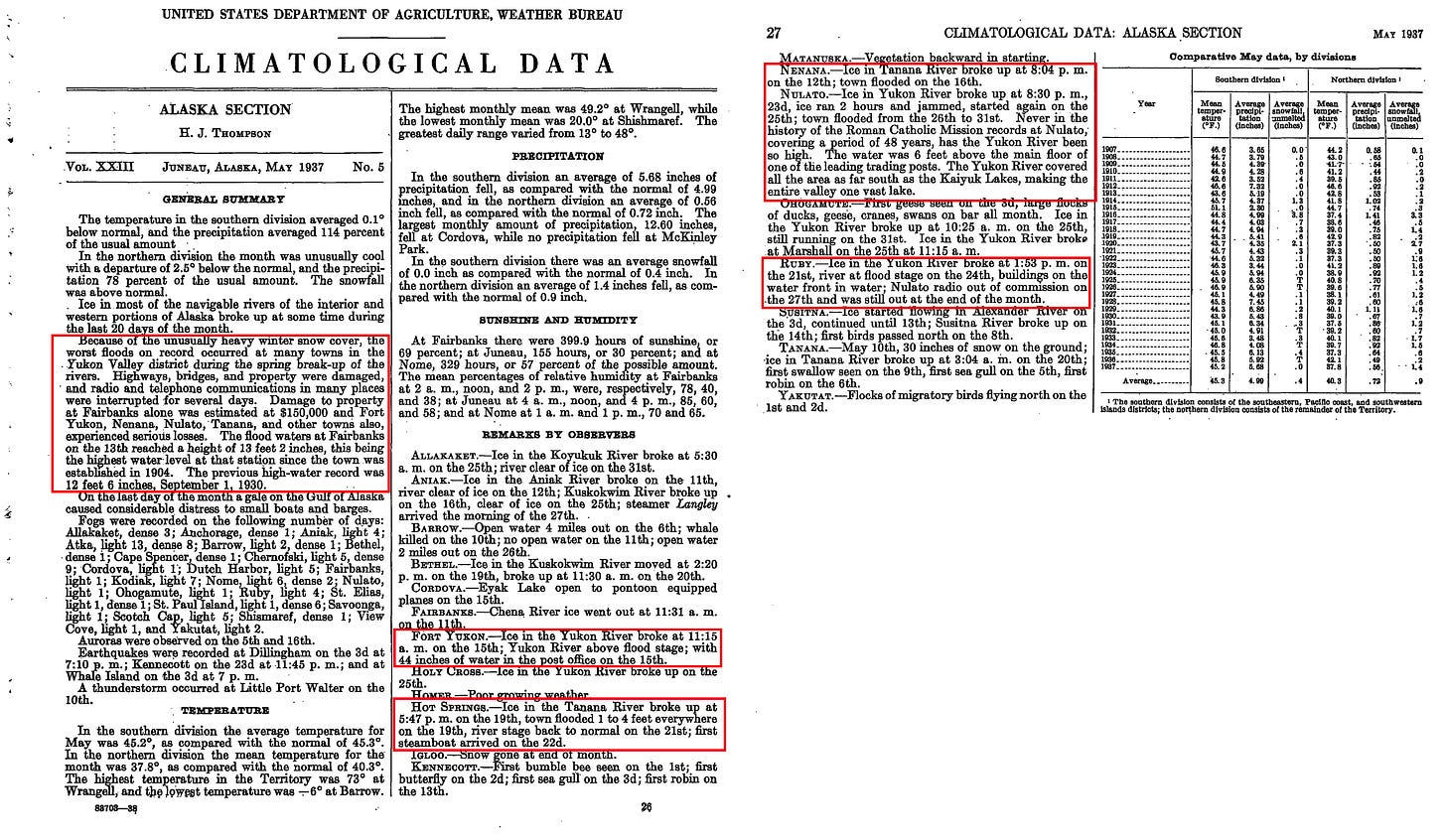

Spring 1937: the winter of 1936-37 brought excessive precipitation to much of mainland Alaska, resulting at least some areas of higher water content in snow pack going into spring than have occurred in modern times when there some measurements or reconstructions. This was compounded by a cold April and the result was severe flooding in many areas. Figure 1 provides a sampling of the impacts that the Weather Bureau was aware of when May 1937 edition of Climatological Data went to press some months later.

Spring 1945 was quite cold and flooding was especially severe on the Yukon River; in some places the flooding was reported to be worse than 1937. Figure 4 is a clip of the summary published in Climatological Data.

April 1948 was cold and very snowy in Interior Alaska. This preceded one of the worst break-up floods in Fairbanks, when in mid-May about 30 percent of the city flooded and property damage was estimated at around $300,000 (~$3.5 million in 2023).

Spring 1964 was very cold, especially in late April and May. There was severe flooding in places along the middle and upper Kuskokwim River in late May and early June, including at Sleetmute, Red Devil and Akiak.

April 1985 was exceptionally cold over most of mainland Alaska: flooding occurred in the Kuskokwim, Tanana Valley and middle Yukon River valleys. The Chena River flood control project was operated to reduce high water impacts in Fairbanks.

April 2009 started off chilly but temperatures rose to near record high levels the last week of the month, with severe flooding on the Yukon River at Eagle and Eagle Village.

Spring 2013 was cold through mid-May. Flooding on the Yukon River was widespread but was especially impactful at Circle City and there was devastating flooding at Galena, as seen in Fig. 5 below.

Ingredients for Serious Break-up Flooding

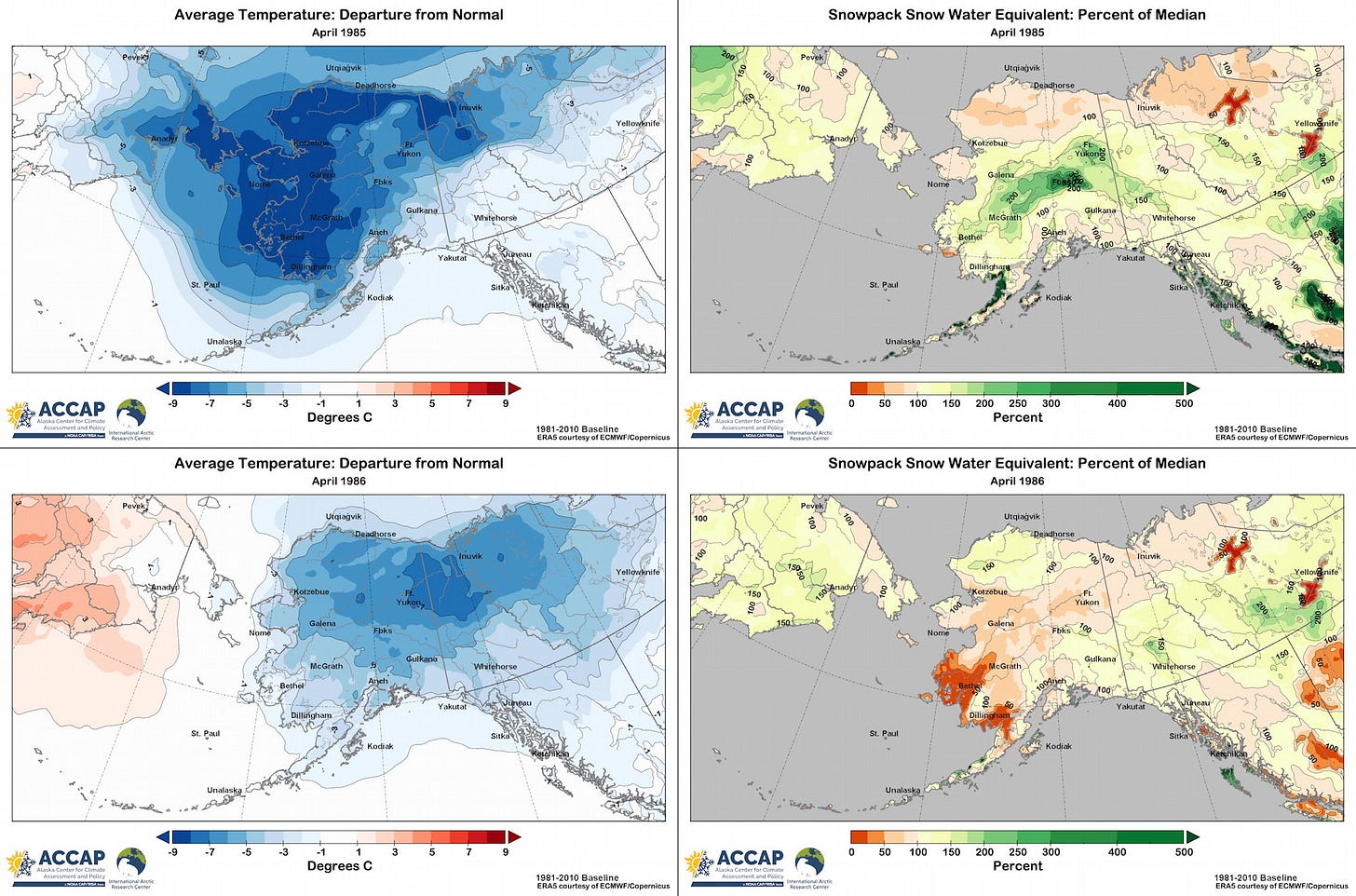

Just scanning through the selection of Springs with significant flooding it’s clear that temperatures play a role: a cold April means that there is little or no snow pack melting even as average temperature climb. Ice jams preferentially form at bends in rivers and where the slope of the river bed changes abruptly. But there is also a random component of where ice jams form (or don’t) and especially of how long the jams hold. So at least localized significant flooding is possible in any Spring, and conversely, even when conditions seem right for ice jams to form they may not. But in the long run, the chances for ice jam flooding go up dramatically when April is cold AND there is a deep snow pack in place going into the melt season. The importance of both factors was nicely illustrated in the consecutive springs of 1985 and 1986. May 1985 brought significant break-up flooding on multiple rivers. In Spring 1986 there was no significant flooding anywhere. In both years April was much colder than normal all across mainland Alaska. In western Alaska, 1985 was colder, in the central Interior and Southcentral the years were not too different, and in the eastern Interior and the Yukon Territory April 1986 was cooler than April 1985, as shown in Fig 6.

Figure 7 compares average temperatures and snow pack for the two years (April 1985 top row, April 1986 bottom row). The big difference was in the snow pack (right). From ERA5 reanalysis, April 1985 saw well above normal snow pack almost everywhere between the Alaska Range and Brooks Range, with the Yukon Flats, lower Tanana and upper Kuskokwim valleys with more than twice the normal snow water equivalent (upper right). In contrast, April 1986 had near to below normal snow pack, in spite of the delayed melting due to the cold temperatures (lower right).

This highlights the importance of both the temperature and snow pack component to Spring break-up flooding. Spring 2023 solidly falls into the “below normal temperature and high snow pack” category and we’ll soon know if this year joins the list of bad break-up Springs.