Days are rapidly lengthening in the North now but there is still plenty of winter weather ahead. Here's an update on 50-year mid-winter (December through February) climate trends. As usual, there's nothing magical about 50 years for a climate trend analysis. It's long enough to remove short term impacts of El Niño/La Niña cycles but short enough to be within an individual's personal memory.

Temperature

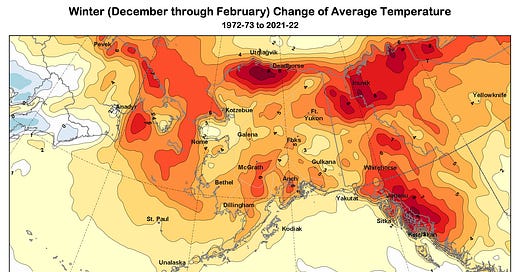

Temperatures over the past half century are trending up everywhere in Alaska and northwest Canada (Fig 1a for the 50-year change in °F, Fig 1b for changes in °C). Overall the largest changes are across the north, from inland North Slope eastward to the northern Yukon Territory to then to east of Inuvik, NWT. The other feature that stands out is the large warming along much of the mountainous Southeast Alaska-British Columbia border. The effect of declining of sea ice is not as prominent in the temperature change pattern in mid-winter as in autumn, but is responsible for the large increases through the Bering Strait and in the Gulf of Anadyr.

Precipitation

Mid-winter precipitation is increasing virtually everywhere in Alaska and northwest Canada, though along the Gulf of Alaska coast and parts of the Interior and southwest Alaska the increases are not large (Fig. 2). The widespread extent of increasing winter precipitation suggests that this not the result of multi-decade storm track changes but rather is consistent with what we expect to happen at high latitudes in a world with warming atmosphere and warming oceans.

Snowfall

Snowfall during mid-winter is increasing over much of mainland Alaska, consistent with increasing precipitation (Fig. 3). In many areas south of the Brooks Range the increase in winter snow is roughly balancing out the decrease in autumn snow. However, along the Gulf of Alaska coast, winter snowfall shows little change at this scale, and across the outer coasts of Southeast and over the Aleutian Islands, snowfall is decreasing even as average precipitation is steady or increases. These are areas where the winter average temperatures at low elevations are already near or above freezing, so even a small increase in temperature changes the phase of precipitation from snow to rain.